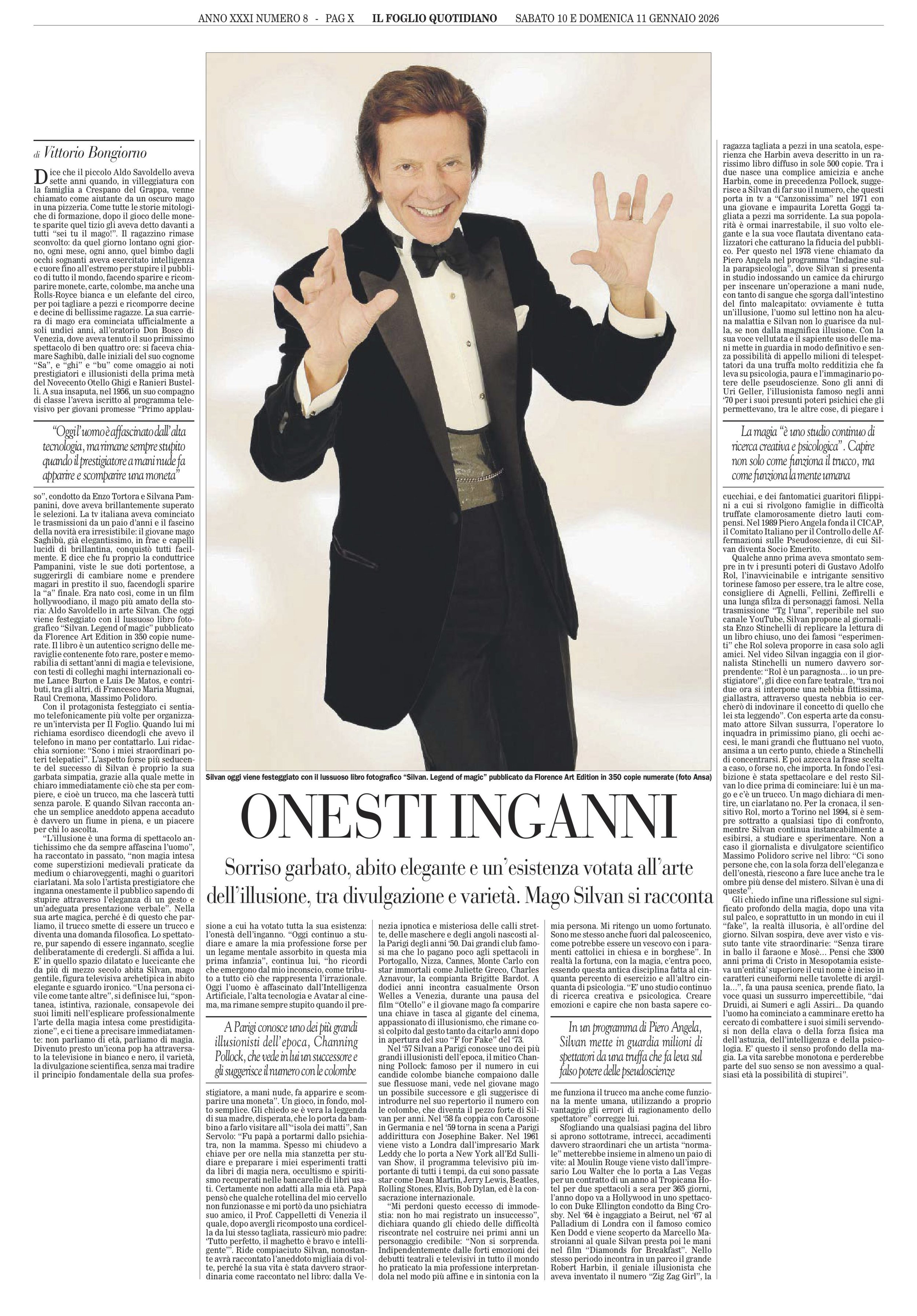

SILVAN. ONESTI INGANNI. /

MICAH P HINSON. VOCE DAL TEXAS. /

STORIA SEGRETA DEI SOLITI IGNOTI /

INARRITU. SCARTI DI GENIO. /

YPSIGROCK. TENERO ROCK. /

LOU REED. LA STELLA DEL MALESSERE. /

JIM JARMUSCH. IL CINEMA DELLE STRADE PERDUTE. /

IL FUTURO È IN UN ARCHIVIO /

inVISIBILI. LE ANTENATE DEL CINEMATOGRAFO. /

THE INVISIBLE ONES

Italy’s Forgotten Women of Early Cinema

“They even did some good things,” my grandmother used to say, referring to the rationalist architecture of Rome’s EUR district, the Treccani Encyclopaedia and what she called the cinematograph—all products of the Fascist Ventennio. Arguments that were, and remain, hard to defend, but which perhaps contained a grain of historical truth now largely acknowledged. Yet it was precisely the Seventh Art—as the Apulian-Parisian polymath Ricciotto Canudo christened it—born in Italy with the creation of the Istituto Luce (1924), Cinecittà (1937) and the Venice Film Festival (1935), that went on to generate intergenerational dreams and become one of the pillars of national culture. Cinema shaped Italian society and exported the immortal divas of silent film and the country’s great directors to the world.

As everyone knows, the cinematograph was patented by the French brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière, who in 1895 astonished Paris with their public screening of La Sortie des usines—workers leaving a factory. Around the same time in the United States, inventor William Kennedy Laurie Dickson shot Dickson Greeting, a twelve-second clip in which he politely tips his hat to an imaginary audience.

Italy’s first film, The Taking of Rome, of which only fragments survive, was shot in 1905 by Filoteo Alberini. Few people know that until the 1930s the word film in Italian was feminine—la film—a direct translation of pellicola. My grandmother would say, “We’ve seen a beautiful pellicola,” never “a beautiful film.” Even Leonardo Sciascia, speaking about cinema, would say, “We’ve seen a beautiful parte,” meaning a beautiful movie.

What almost no one remembers, however, is that from the dawn of silent cinema to the early 1940s, women were pioneers and leading figures in Italian film—not only as actresses, but also as directors, screenwriters, editors, costume designers and even distributors of their own work. Unthinkable then—and, in many ways, still unthinkable today.

This forgotten and perhaps deliberately obscured history is brought back to light by the exhibition inVisibili. The Women Pioneers of Cinema, promoted by the Italian Ministry of Culture and produced by Archivio Luce Cinecittà thanks to the passionate commitment of Undersecretary for Culture Lucia Borgonzoni and Cinecittà President Chiara Sbarigia. From 16 May to 28 September 2025, crossing the threshold of Rome’s Istituto Centrale per la Grafica feels like stepping into a time machine—one that revives the dazzling adventures and remarkable virtues of thirty extraordinary women whose stories were erased from official narratives.

Those narratives, with few exceptions, have handed down to history only male protagonists, forgetting to acknowledge figures such as Elvira Notari, Francesca Bertini, Adriana Costamagna, Frieda Klug, Esterina Zuccarone, Astrea, Gemma Bellincioni, Daist Sylvan and Paola Pezzaglia Greco—women who conquered roles and visibility, shattered a male-dominated power structure and wrote crucial chapters of Italian cinema. Names known today mostly to a handful of passionate scholars willing to dig deep into what is truly a well of surprises.

“Divas in the 1910s were the ‘owners’ of Italian cinema, to the point that their roles often went far beyond acting and into co-authorship,” writes Culture Minister Alessandro Giuli in the Electa catalogue. “It is right to return in memory to women who asserted themselves in a world where they were not fully recognised and did not even enjoy full civil and political rights—rare examples of courage and dignity.” Borgonzoni echoes him, noting that “making them visible again is an exciting challenge that allows us to look at our cinema’s history from another, less obvious and more truthful angle: a story of both men and women.”

We do know the feats of silent-era divas like Italia Almirante Manzini—cousin of politician Giorgio—who played Sophonisba in the first Italian blockbuster Cabiria (1914), directed by Giovanni Pastrone and scripted by Gabriele D’Annunzio. Or Eleonora Duse, one of the greatest theatre actresses of all time, who made a single foray into film with Cenere (1916). But the heart of the exhibition is dedicated to women who overcame financial, cultural, social and political obstacles to write, direct, produce, edit and even distribute their own films.

The most striking case is Elvira Notari (1875–1946). She began shooting films in the backstreets of Naples using real people—street kids, tough guys, fishermen—anticipating neorealism by more than twenty years. In 1912 she founded Dora Film and went on to direct over sixty feature films. Too raw and too real for the Fascist regime, her work eventually clashed openly with power. In 1925 she sailed to New York, opening Dora Film of America on Seventh Avenue and finding huge success among Italian-American audiences. But sound and colour soon made her artisanal approach unsustainable. Dora Film closed in 1930. Elvira returned to southern Italy and died in 1946—almost entirely forgotten.

Then there is Francesca Bertini (1892–1985), perhaps the most iconic diva of all. Born to a single mother, she rose from Neapolitan theatre to international fame with films like Assunta Spina (1915). The word diva was coined for her. With the highest fees in silent Italian cinema, she negotiated scripts, editing and the entire creative process, even founding her own production company in 1918. Fox wanted her in Hollywood; she declined. The arrival of sound, however, marked her decline. Bernardo Bertolucci would later bring her back for a final appearance in 1900 (1976). Then silence fell again.

And what about Adriana Costamagna (1889–1958), mauled and disfigured by a real leopard on set, who thereafter appeared veiled in public, turning tragedy into legend—and founded her own production company anyway? Or Elvira Giallanella, who in 1920 made Umanità, a pacifist dream shot on the war-scarred Karst plateau, then lost for nearly ninety years before being rediscovered and restored?

Thinking of cinema as “a man’s job” or “a woman’s job” is a sterile exercise. But inVisibili fills a gaping hole in our collective memory, restoring space, voice and names to fearless women who were not background figures but bold protagonists of a newborn industry. Their stories, studied today with curiosity and without prejudice, are powerful lessons for future generations.

“They appear freer,” writes Carlo Chatrian, director of the National Museum of Cinema in Turin. “They drive cars, smoke, ride horses and balloons, wear daring clothes, dictate the pace of courtship. Sometimes they even underestimate the risks of the scene.”

They did do some good things, yes. I wonder what my grandmother would think today of those brave, beautiful women. And I wonder whether my female filmmaker friends will go and see the exhibition—perhaps to discover extraordinary grandmothers, aunts and friends they never knew they had.